Setting Up Endowment Spending Policies for Long-Term Sustainability

Endowments Vary In Size, and Play a Critical Role in University Finances

Endowments are the pool of invested funds, typically seeded by donations to colleges and universities from private benefactors to support the long-term sustainability of the institutional mission. These endowments have grown to become a massive component of university budgets. Harvard University, for example, has an endowment that has ballooned to $53 billion as of 2024. Their target annual distribution is roughly 5%, which means that their endowment spins out over $2.5 billion in dollars they can spend every year (a number that has been growing just about every year). On the other hand, most universities don't command $50+ billion endowments; in fact, 56% of public and 61% of private nonprofit four-year institutions had endowments <$50 million (or had no endowment altogether). About a quarter of four-year schools had endowments under $10 million in total. Because the spending rate typically stays roughly the same (a topic we'll dive into further), some institutions can fund sizable portions of their annual operating budget, and others cannot. On average, institutions with endowments used the funds to support about ~15% of their annual operating expenses. This is a critical source of revenue in any year; most particularly in today's age where tuition is under pressure, enrollment cliffs are upon us and federal support is declining. These funds serve a critical function in the support of student scholarships, faculty salaries, instruction and other operating expenses.

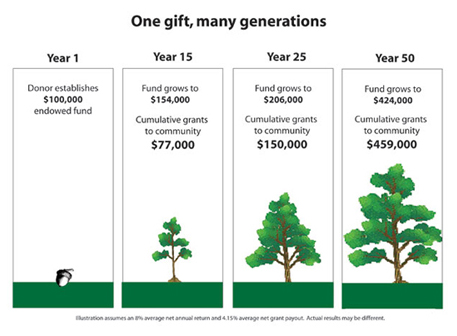

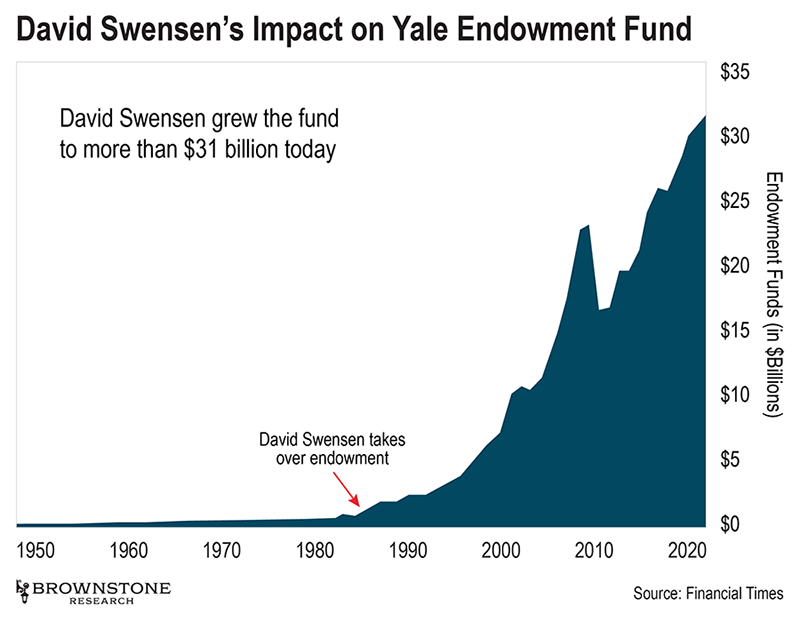

Because endowments are perhaps the best, or at least the most striking, example of the power of compound interest, they are also examples of the power law. About 150 universities have endowments in excess of $1 billion in total assets as of 2024, which comprise roughly 86% of total U.S. endowment assets (keep in mind there are ~4,000 public + private universities across the U.S.). As time moves on, it's likely (absent significant regulatory changes), that the large endowments will continue to get larger, and those institutions will continue to differentially benefit versus institutions with smaller endowments. A famous example is Yale's endowment, which was overseen by famed endowment investor David Swensen, who saw average performance of almost 14% over his 36-year tenure at the Yale endowment. Outperformance like that gives you charts like these:

Now, depending on Yale's spending policies, that chart could have looked a lot worse. We'll explore why in the next section.

Endowment-Wide Spending Policies: Spend Now vs. Invest For Later?

Perhaps the single most important question to evaluate each year is the spending rate. The spending rate is the percentage of the market value of the endowment that is set aside to be spent each year. For example, an endowment of $100M in total assets might have a spend rate of about 4-5% per year, which would allow for $4M - $5M in annual operating funds. Spend too much, and you take away from the future growth of the endowment. Spend too little, and you may see financial strain in your annual operations.

To help you visualize the differences, we've put together a simple tool to project the implications of your spending rate on your annual and long-term institutional goals:

endowmentspending.vercel.app

To think this through, let's talk through a couple of scenarios.

In scenario 1, you set your spending rate to be equal to your investment returns. This is generally the maximum spending rate you could presumably set, and for good reason, is almost never actually employed at any endowment committee. This maximizes the annual operating budget, but it completely cuts off your long-term endowment growth. Your endowment will only ever grow based on new gifts, and you're not letting long-term capital compounding provide your institution with any gains. If you take an annual investment return of 7%, and assume your endowment starts this year at $100M in assets, you are sacrificing $X in long term growth. Not only does this sacrifice long-term growth, but it also puts the endowment at the mercy of inflation, and for these reasons, there are often policies (both self-imposed and sometimes donor-imposed) to ensure more cushion between the annual spend rate of the endowment and investment performance. To further accentuate this point, if Yale had taken their spending rate up to the investment performance achieved by David Swensen and his team, Yale's endowment would be a small fraction of the chart shown above - a decision that would have ultimately cost them billions over time.

In scenario 2, you set your spending rate to be 3.5% (about half of your expected investment returns over a 10-year period). Generally, this is a good balance between short term operating needs and long-term sustainable growth of the endowment. Here's a problem though: what happens if one year, the endowment falls by 20% in value? Sounds scary - but it's happened. In the 2008 financial crisis, many universities saw their endowments fall by about a quarter of their value - some around 30% even. And because so many endowments have significant exposure to private and illiquid asset classes, they can really struggle to liquidate assets for operating budgets, sometimes selling at further losses at the exact wrong moment. This is one reason why most endowments will have some sort of smoothing function whereby they take the average of the last 3 years or so of investment performance when making their spending rate determinations.

If we look at the data, most institutions typically target a range between 4 - 5% of their endowment's market value to be spent each year. Some institutions that have commanded above average annual investment performance might further increase this; for example, Yale's spending rate is typically around 5.25%. But broadly speaking, institutions rarely deviate significantly from these ranges over the long term.

Now, occasionally, some institutions do get approval for extra draws from the endowment. These are typically short-term and more-or-less one-time. Typically they require not only board approval but oftentimes require significant communication with donors. These one-time draws are typically for bridge funding in extenuating circumstances (i.e., COVID and internal/external financial crises).

Fund-Specific Spending Policies & UPMIFA

So far we've been largely pretending that all endowed funds within an institution are managed the same. But we have to keep in mind that endowments are created all the time, and depending on their funding timeline and restrictions, they may need to be managed a little differently. For one thing, some funds don't get spent down at all in a year; depending on how often this happens, it can affect the average spending rate of the endowment. Also, usually, endowed funds don't usually start getting spent down immediately. There's usually some grace period where the endowment has to grow to a certain size or for a certain period of time before the investment performance begins to get spent. For example, if a donor gives a $100M gift but the first year it's invested, the endowment falls in value by 20%, institutions (and donors) typically don't want to eat into the $80M remaining principal, and instead want to wait until the market value reaches back to $100M or even $125M before being spent.

UPMIFA (the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act) is a legal framework adopted with some variations across all 50 states. This framework modernized earlier laws governing charitable endowments and set clearer guidelines for how these funds should be spent.

UPMIFA, for example, overturns a prior rule from a similar framework from 1972 (called UMIFA), where so-called "underwater" endowments (where the market value is below the original book value / sum of gifts made) could not be legally spent at all. This provided institutions with more flexibility - for example, they could now use their endowed funds in moments of financial crisis where there funds may be needed most. Instead, UPMIFA set a "prudence standard" which allows institutional governing boards to make good-faith decisions that such an expenditure is prudent and consisten with the donor's intent and the purpose of the fund. Specific states have various factors or policies as to how this standard is evaluated and upheld, but allow for a more flexible, case-by-case approach than the prior framework.

Another pertinent component has to due with explicit donor restrictions involved in these gifts. If a donor’s gift agreement explicitly forbids spending below the original gift (or sets a strict payout limit), the institution must abide by those terms. UPMIFA does contain mechanisms for modifying or releasing old restrictions (for example, via donor consent or court approval under certain conditions), but such steps are taken carefully. In general, boards will try to work within the donor’s stipulations; UPMIFA’s spending provisions apply mainly when the gift instrument is silent on specifics. Thus, if a donor simply says “hold this as an endowment” without more detail, UPMIFA’s prudent spending rules govern by default. But if a donor contractually required, say, that only the interest can be spent and the principal must remain intact, that restriction remains in force unless legally amended. Colleges therefore must review each endowment fund’s terms before deciding on spending, especially in underwater scenarios, to ensure they don’t violate donor agreements (while still adhering to federal and state specific mandates - particularly relevant in today's context).

Finally, it’s worth noting the external pressures and scrutiny on endowment management. Policymakers and the public occasionally question whether universities are using their endowments optimally to advance affordability and access. As mentioned, in the late 2000s Congressional committees raised the idea of mandating minimum payout rates for university endowments (analogous to private foundations’ 5% rule). While no such payout mandate was enacted, a federal excise tax on large endowments was introduced in 2017: colleges enrolling over 500 students and having endowment assets exceeding $500,000 per student are subject to a 1.4% tax on their annual investment income. This effectively targeted only the richest institutions (initially about 25–30 universities). In recent years, proposals have surfaced to raise this endowment tax – for example, to 10% of investment income and lowering the asset threshold to $200,000 per student, which would capture many more institutions. Another proposal even suggested a 21% tax.

University leaders and groups like NACUBO have strongly opposed such measures, arguing that taxing endowment earnings “diminishes the charitable resources that would otherwise be available” for student aid, research, and educational programs. They point out that endowment funds are meant for public benefit (through education and scholarships) and that forced depletion or additional taxes could undermine universities’ ability to support students long-term. This debate is ongoing, reflecting a tension between the desire to see wealthy colleges spend more now (for example, to offset tuition hikes or public funding cuts) and the principle of preserving endowments for sustained impact. Nonetheless, across the board, U.S. colleges have in fact been increasing their endowment spending in recent years – endowment distributions grew to a collective $30 billion in FY2024, nearly half of which directly underwrote student financial aid. Even amid economic uncertainties, most institutions strive to use their endowments as they were intended: to support students, faculty, and the academic mission in perpetuity – prudently managing these funds so that they can weather market downturns and continue benefiting both current and future generations of students.

Transform your scholarship awarding & stewardship with Awarded

Attract & retain more students and donors starting today.

.png)

.png)